Remarks by Chairman Ben S. BernankeAt the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City's Thirtieth Annual Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole, WyomingAugust 25, 2006 Global Economic Integration: What's New and What's Not?When geographers study the earth and its features, distance is one of the basic measures they use to describe the patterns they observe. Distance is an elastic concept, however. The physical distance along a great circle from Wausau, Wisconsin to Wuhan, China is fixed at 7,020 miles. But to an economist, the distance from Wausau to Wuhan can also be expressed in other metrics, such as the cost of shipping goods between the two cities, the time it takes for a message to travel those 7,020 miles, and the cost of sending and receiving the message. Economically relevant distances between Wausau and Wuhan may also depend on what trade economists refer to as the "width of the border," which reflects the extra costs of economic exchange imposed by factors such as tariff and nontariff barriers, as well as costs arising from differences in language, culture, legal traditions, and political systems. One of the defining characteristics of the world in which we now live is that, by most economically relevant measures, distances are shrinking rapidly. The shrinking globe has been a major source of the powerful wave of worldwide economic integration and increased economic interdependence that we are currently experiencing. The causes and implications of declining economic distances and increased economic integration are, of course, the subject of this conference. The pace of global economic change in recent decades has been breathtaking indeed, and the full implications of these developments for all aspects of our lives will not be known for many years. History may provide some guidance, however. The process of global economic integration has been going on for thousands of years, and the sources and consequences of this integration have often borne at least a qualitative resemblance to those associated with the current episode. In my remarks today I will briefly review some past episodes of global economic integration, identify some common themes, and then put forward some ways in which I see the current episode as similar to and different from the past. In doing so, I hope to provide some background and context for the important discussions that we will be having over the next few days. A Short History of Global Economic IntegrationAs I just noted, the economic integration of widely separated regions is hardly a new phenomenon. Two thousand years ago, the Romans unified their far-flung empire through an extensive transportation network and a common language, legal system, and currency. One historian recently observed that "a citizen of the empire traveling from Britain to the Euphrates in the mid-second century CE would have found in virtually every town along the journey foods, goods, landscapes, buildings, institutions, laws, entertainment, and sacred elements not dissimilar to those in his own community." (Hitchner, 2003, p. 398). This unification promoted trade and economic development. A millennium and a half later, at the end of the fifteenth century, the voyages of Columbus, Vasco da Gama, and other explorers initiated a period of trade over even vaster distances. These voyages of discovery were made possible by advances in European ship technology and navigation, including improvements in the compass, in the rudder, and in sail design. The sea lanes opened by these voyages facilitated a thriving intercontinental trade--although the high costs of and the risks associated with long voyages tended to limit trade to a relatively small set of commodities of high value relative to their weight and bulk, such as sugar, tobacco, spices, tea, silk, and precious metals. Much of this trade ultimately came under the control of the trading companies created by the English and the Dutch. These state-sanctioned monopolies enjoyed--and aggressively protected--high markups and profits. Influenced by the prevailing mercantilist view of trade as a zero-sum game, European nation-states competed to dominate lucrative markets, a competition that sometimes spilled over into military conflict. The expansion of international trade in the sixteenth century faced some domestic opposition. For example, in an interesting combination of mercantilist thought and social commentary, the reformer Martin Luther wrote in 1524: "But foreign trade, which brings from Calcutta and India and such places wares like costly silks, articles of gold, and spices--which minister only to ostentation but serve no useful purpose, and which drain away the money of the land and people--would not be permitted if we had proper government and princes... God has cast us Germans off to such an extent that we have to fling our gold and silver into foreign lands and make the whole world rich, while we ourselves remain beggars." (James, 2001, p. 8) Global economic integration took another major leap forward during the period between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the beginning of World War I. International trade again expanded significantly as did cross-border flows of financial capital and labor. Once again, new technologies played an important role in facilitating integration: Transport costs plunged as steam power replaced the sail and railroads replaced the wagon or the barge, and an ambitious public works project, the opening of the Suez Canal, significantly reduced travel times between Europe and Asia. Communication costs likewise fell as the telegraph came into common use. One observer in the late 1860s described the just completed trans-Atlantic telegraph cable as having "annihilated both space and time in the transmission of intelligence" (Standage, 1998, p. 90). Trade expanded the variety of available goods, both in Europe and elsewhere, and as the trade monopolies of earlier times were replaced by intense competition, prices converged globally for a wide range of commodities, including spices, wheat, cotton, pig iron, and jute (Findlay and O'Rourke, 2002). The structure of trade during the post-Napoleonic period followed a "core-periphery" pattern. Capital-rich Western European countries, particularly Britain, were the center, or core, of the trading system and the international monetary system. Countries in which natural resources and land were relatively abundant formed the periphery. Manufactured goods, financial capital, and labor tended to flow from the core to the periphery, with natural resources and agricultural products flowing from the periphery to the core. The composition of the core and the periphery remained fairly stable, with one important exception being the United States, which, over the course of the nineteenth century, made the transition from the periphery to the core. The share of manufactured goods in U.S. exports rose from less than 30 percent in 1840 to 60 percent in 1913, and the United States became a net exporter of financial capital beginning in the late 1890s.1 For the most part, government policies during this era fostered openness to trade, capital mobility, and migration. Britain unilaterally repealed its tariffs on grains (the so-called corn laws) in 1846, and a series of bilateral treaties subsequently dismantled many barriers to trade in Europe. A growing appreciation for the principle of comparative advantage, as forcefully articulated by Adam Smith and David Ricardo, may have made governments more receptive to the view that international trade is not a zero-sum game but can be beneficial to all participants. That said, domestic opposition to free trade eventually intensified, as cheap grain from the periphery put downward pressure on the incomes of landowners in the core. Beginning in the late 1870s, many European countries raised tariffs, with Britain being a prominent exception. Britain did respond to protectionist pressures by passing legislation that required that goods be stamped with their country of origin. This step provided additional grist for trade protesters, however, as the author of one British anti-free-trade pamphlet in the 1890s lamented that even the pencil he used to write his protest was marked "made in Germany" (James, 2001, p. 15). In the United States, tariffs on manufactures were raised in the 1860s to relatively high levels, where they remained until well into the twentieth century. Despite these increased barriers to the importation of goods, the United States was remarkably open to immigration throughout this period. Unfortunately, the international economic integration achieved during the nineteenth century was largely unraveled in the twentieth by two world wars and the Great Depression. After World War II, the major powers undertook the difficult tasks of rebuilding both the physical infrastructure and the international trade and monetary systems. The industrial core--now including an emergent Japan as well as the United States and Western Europe--ultimately succeeded in restoring a substantial degree of economic integration, though decades passed before trade as a share of global output reached pre-World War I levels. One manifestation of this re-integration was the rise of so-called intra-industry trade. Researchers in the late-1960s and the 1970s noted that an increasing share of global trade was taking place between countries with similar resource endowments, trading similar types of goods--mainly manufactured products traded among industrial countries.2 Unlike international trade in the nineteenth century, these flows could not be readily explained by the perspectives of Ricardo or of the Swedish economists Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin that emphasized national differences in endowments of natural resources or factors of production. In influential work, Paul Krugman and others have since argued that intra-industry trade can be attributed to firms' efforts to exploit economies of scale, coupled with a taste for variety by purchasers. Postwar economic re-integration was supported by several factors, both technological and political. Technological advances further reduced the costs of transportation and communication, as the air freight fleet was converted from propeller to jet and intermodal shipping techniques (including containerization) became common. Telephone communication expanded, and digital electronic computing came into use. Taken together, these advances allowed an ever-broadening set of products to be traded internationally. In the policy sphere, tariff barriers--which had been dramatically increased during the Great Depression--were lowered, with many of these reductions negotiated within the multilateral framework provided by the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Globalization was, to some extent, also supported by geopolitical considerations, as economic integration among the Western market economies became viewed as part of the strategy for waging the Cold War. However, although trade expanded significantly in the early post-World War II period, many countries--recalling the exchange-rate and financial crises of the 1930s--adopted regulations aimed at limiting the mobility of financial capital across national borders. Several conclusions emerge from this brief historical review. Perhaps the clearest conclusion is that new technologies that reduce the costs of transportation and communication have been a major factor supporting global economic integration. Of course, technological advance is itself affected by the economic incentives for inventive activity; these incentives increase with the size of the market, creating something of a virtuous circle. For example, in the nineteenth century, the high potential return to improving communications between Europe and the United States prompted intensive work to better understand electricity and to improve telegraph technology--efforts that together helped make the trans-Atlantic cable possible. A second conclusion from history is that national policy choices may be critical determinants of the extent of international economic integration. Britain's embrace of free trade and free capital flows helped to catalyze international integration in the nineteenth century. Fifteenth-century China provides an opposing example. In the early decades of that century, the Chinese sailed great fleets to the ports of Asia and East Africa, including ships much larger than those that the Europeans were to use later in the voyages of discovery. These expeditions apparently had only limited economic impact, however. Ultimately, internal political struggles led to a curtailment of further Chinese exploration (Findlay, 1992). Evidently, in this case, different choices by political leaders might have led to very different historical outcomes. A third observation is that social dislocation, and consequently often social resistance, may result when economies become more open. An important source of dislocation is that--as the principle of comparative advantage suggests--the expansion of trade opportunities tends to change the mix of goods that each country produces and the relative returns to capital and labor. The resulting shifts in the structure of production impose costs on workers and business owners in some industries and thus create a constituency that opposes the process of economic integration. More broadly, increased economic interdependence may also engender opposition by stimulating social or cultural change, or by being perceived as benefiting some groups much more than others. The Current Episode of Global Economic IntegrationHow does the current wave of global economic integration compare with previous episodes? In a number of ways, the remarkable economic changes that we observe today are being driven by the same basic forces and are having similar effects as in the past. Perhaps most important, technological advances continue to play an important role in facilitating global integration. For example, dramatic improvements in supply-chain management, made possible by advances in communication and computer technologies, have significantly reduced the costs of coordinating production among globally distributed suppliers. Another common feature of the contemporary economic landscape and the experience of the past is the continued broadening of the range of products that are viewed as tradable. In part, this broadening simply reflects the wider range of goods available today--high-tech consumer goods, for example--as well as ongoing declines in transportation costs. Particularly striking, however, is the extent to which information and communication technologies now facilitate active international trade in a wide range of services, from call center operations to sophisticated financial, legal, medical, and engineering services. The critical role of government policy in supporting, or at least permitting, global economic integration, is a third similarity between the past and the present. Progress in trade liberalization has continued in recent decades--though not always at a steady pace, as the recent Doha Round negotiations demonstrate. Moreover, the institutional framework supporting global trade, most importantly the World Trade Organization, has expanded and strengthened over time. Regional frameworks and agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement and the European Union's "single market," have also promoted trade. Government restrictions on international capital flows have generally declined, and the "soft infrastructure" supporting those flows--for example, legal frameworks and accounting rules--have improved, in part through international cooperation. In yet another parallel with the past, however, social and political opposition to rapid economic integration has also emerged. As in the past, much of this opposition is driven by the distributional impact of changes in the pattern of production, but other concerns have been expressed as well--for example, about the effects of global economic integration on the environment or on the poorest countries. What, then, is new about the current episode? Each observer will have his or her own perspective, but, to me, four differences between the current wave of global economic integration and past episodes seem most important. First, the scale and pace of the current episode is unprecedented. For example, in recent years, global merchandise exports have been above 20 percent of world gross domestic product, compared with about 8 percent in 1913 and less than 15 percent as recently as 1990; and international financial flows have expanded even more quickly.3 But these data understate the magnitude of the change that we are now experiencing. The emergence of China, India, and the former communist-bloc countries implies that the greater part of the earth's population is now engaged, at least potentially, in the global economy. There are no historical antecedents for this development. Columbus's voyage to the New World ultimately led to enormous economic change, of course, but the full integration of the New and the Old Worlds took centuries. In contrast, the economic opening of China, which began in earnest less than three decades ago, is proceeding rapidly and, if anything, seems to be accelerating. Second, the traditional distinction between the core and the periphery is becoming increasingly less relevant, as the mature industrial economies and the emerging-market economies become more integrated and interdependent. Notably, the nineteenth-century pattern, in which the core exported manufactures to the periphery in exchange for commodities, no longer holds, as an increasing share of world manufacturing capacity is now found in emerging markets. An even more striking aspect of the breakdown of the core-periphery paradigm is the direction of capital flows: In the nineteenth century, the country at the center of the world's economy, Great Britain, ran current account surpluses and exported financial capital to the periphery. Today, the world's largest economy, that of the United States, runs a current-account deficit, financed to a substantial extent by capital exports from emerging-market nations. Third, production processes are becoming geographically fragmented to an unprecedented degree.4 Rather than producing goods in a single process in a single location, firms are increasingly breaking the production process into discrete steps and performing each step in whatever location allows them to minimize costs. For example, the U.S. chip producer AMD locates most of its research and development in California; produces in Texas, Germany, and Japan; does final processing and testing in Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and China; and then sells to markets around the globe. To be sure, international production chains are not entirely new: In 1911, Henry Ford opened his company's first overseas factory in Manchester, England, to be closer to a growing source of demand. The factory produced bodies for the Model A automobile, but imported the chassis and mechanical parts from the United States for assembly in Manchester. Although examples like this one illustrate the historical continuity of the process of economic integration, today the geographical extension of production processes is far more advanced and pervasive than ever before. As an aside, some interesting economic questions are raised by the fact that in some cases international production chains are managed almost entirely within a single multinational corporation (roughly 40 percent of U.S. merchandise trade is classified as intra-firm) and in others they are built through arm's-length transactions among unrelated firms. But the empirical evidence in both cases suggests that substantial productivity gains can often be achieved through the development of global supply chains.5 The final item on my list of what is new about the current episode is that international capital markets have become substantially more mature. Although the net capital flows of a century ago, measured relative to global output, are comparable to those of the present, gross flows today are much larger. Moreover, capital flows now take many more forms than in the past: In the nineteenth century, international portfolio investments were concentrated in the finance of infrastructure projects (such as the American railroads) and in the purchase of government debt. Today, international investors hold an array of debt instruments, equities, and derivatives, including claims on a broad range of sectors. Flows of foreign direct investment are also much larger relative to output than they were fifty or a hundred years ago.6 As I noted earlier, the increase in capital flows owes much to capital-market liberalization and factors such as the greater standardization of accounting practices as well as to technological advances. ConclusionBy almost any economically relevant metric, distances have shrunk considerably in recent decades. As a consequence, economically speaking, Wausau and Wuhan are today closer and more interdependent than ever before. Economic and technological changes are likely to shrink effective distances still further in coming years, creating the potential for continued improvements in productivity and living standards and for a reduction in global poverty. Further progress in global economic integration should not be taken for granted, however. Geopolitical concerns, including international tensions and the risks of terrorism, already constrain the pace of worldwide economic integration and may do so even more in the future. And, as in the past, the social and political opposition to openness can be strong. Although this opposition has many sources, I have suggested that much of it arises because changes in the patterns of production are likely to threaten the livelihoods of some workers and the profits of some firms, even when these changes lead to greater productivity and output overall. The natural reaction of those so affected is to resist change, for example, by seeking the passage of protectionist measures. The challenge for policymakers is to ensure that the benefits of global economic integration are sufficiently widely shared--for example, by helping displaced workers get the necessary training to take advantage of new opportunities--that a consensus for welfare-enhancing change can be obtained. Building such a consensus may be far from easy, at both the national and the global levels. However, the effort is well worth making, as the potential benefits of increased global economic integration are large indeed. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------ReferencesBloom, Nick, Raffaella Sadun, and John Van Reenen (2006). "It Ain't What You Do It's the Way That You Do I.T.--Investigating the Productivity Miracle Using the Overseas Activities of U.S. Multinationals," unpublished paper, Centre for Economic Performance, March.Bordo, Michael, Barry Eichengreen, and Douglas Irwin (1999). "Is Globalization Today Really Different than Globalization a Hundred Years Ago?" NBER Working Paper No. 7195, June.Corrado, Carol, Paul Lengermann, and Larry Slifman (2005). "The Contribution of MNCs to U.S. Productivity Growth, 1977-2000," unpublished paper, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, July.Criscuolo, Chiara, and Ralf Martin (2005). "Multinationals and U.S. Productivity Leadership: Evidence from Great Britain," Centre for Economic Performance, Discussion Paper No. 672, January.Doms, Mark E. and J. Bradford Jensen (1998). "Comparing Wages, Skills, and Productivity between Domestically and Foreign-Owned Manufacturing Establishments in the United States," in R.E. Baldwin, R.E. Lipsey, and J. David Richardson, eds., Geography and Ownership as Bases for Economic Accounting, NBER Studies in Income and Wealth, vol. 59, Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press, pp. 235-58.Findlay, Ronald (1992). "The Roots of Divergence: Western Economic History in Comparative Perspective," AEA Papers and Proceedings, vol. 82:2, May, pp. 158-61.Findlay, Ronald, and Kevin O'Rourke (2002). "Commodity Market Integration 1500-2000," Centre for Economic Policy Research, Discussion Paper No. 3125, January.Grubel, Herbert, and P.J. Lloyd (1975). Intra-Industry Trade, New York, New York: John Wiley & Sons.Hanson, Gordon, Raymond Mataloni, and Matthew Slaughter (2005). "Vertical Production Networks in Multinational Firms," Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 87:4, November.Historical Statistics of the United States: Earliest Times to Present (Millennial Edition) (2006). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press.Hitchner, Bruce (2003). "Roman Empire," in Joel Mokyr ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, vol. 4, pp. 397-400.James, Harold (2001) The End of Globalization: Lessons from the Great Depression, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Kurz, Christopher (2006). "Outstanding Outsourcers: A Firm- and Plant-Level Analysis of Production Sharing," Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2006-04, Federal Reserve Board, March.Maddison, Angus (2001). The World Economy: A Millenial Perspective, Paris, France: OECD Development Centre.Standage, Tom (1998). The Victorian Internet, New York, New York: Walker Publishing Company.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Footnotes1. Data are from Historical Statistics of the United States (2006). 2. See, for example, Grubel and Lloyd (1975).3. Maddison (2001) and International Monetary Fund data. 4. See, for example, Hanson, Mataloni, and Slaughter (2005). 5. Some of the key empirical papers in this literature are Doms and Jensen (1998); Criscuolo and Martin (2005); Corrado, Lengermann, and Slifman (2005); Bloom, Sadun, and Van Reenen (2006), and Kurz (2006). 6. See, for example, Bordo, Eichengreen, and Irwin (1999).

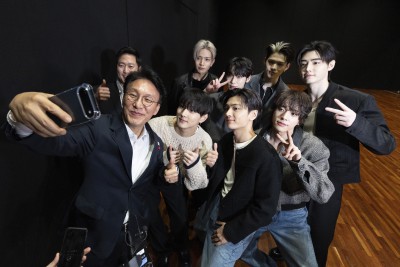

사진

사진

사진

사진